In this post, we will discuss how the Minesweeper module of mimikatz is implemented and code our own version in Rust. The finished crate can be found in the mimisweep repository.

Motivation

I recently picked up the Rust programming language, and I’ve been looking for interesting projects to implement using the language. While I’ve been developing some small crates with simple functionality, I felt like I was prepared to tackle a more ambitious project — maybe the development of a tool that could be useful for real-world Red Team engagements.

As I was browsing projects on GitHub for inspiration, I remembered a piece of advise that I had never actually put to the test:

Re-implement the tools that you commonly use to better understand its underlying functionality.

While it is a deceptively simple rule, we often may be surprised with the complexity of the inner workings of most of the widely-used tools in penetration testing. Analyzing existing code is an excellent way of learning how to perform attacks that may not be very well documented or that we never stopped to theoretically understand. It turns out that it is also a good way of practicing a new programming language: as we are basing our project on an existing codebase, we can shift our focus from the complexity of implementing the desired functionality while practicing our programming skills and learning a thing or two on the way.

Now decided to re-implement an existing tool, I chose to go with the infamous mimikatz, manly for three reasons:

- I wanted to learn in a more in-depth way how

mimikatzinteracts with Windows to carry out its attacks. - It is programmed in C and it makes extensive use of the Windows API, making it a good target for practicing development of offensive Rust tools.

- The source code for

mimikatzits publicly available in thegentilkiwi/mimikatzrepository on GitHub.

As eager to start as I was, I quickly realized that the mimikatz codebase it’s no small feat, with around 30 000 lines of code divided in plenty of similar-looking modules. Even finding in which file a piece of functionality was implemented was tedious for me, as a foreigner to this code.

So instead of diving straight into the more interesting functionality of mimikatz, such as credential enumeration, I decided to analyze one of its most basic modules: the minesweeper module.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

.#####. mimikatz 2.2.0 (x64) #19041 Sep 19 2022 17:44:08

.## ^ ##. "A La Vie, A L'Amour" - (oe.eo)

## / \ ## /*** Benjamin DELPY `gentilkiwi` ( benjamin@gentilkiwi.com )

## \ / ## > https://blog.gentilkiwi.com/mimikatz

'## v ##' Vincent LE TOUX ( vincent.letoux@gmail.com )

'#####' > https://pingcastle.com / https://mysmartlogon.com ***/

mimikatz # minesweeper::

ERROR mimikatz_doLocal ; "(null)" command of "minesweeper" module not found !

Module : minesweeper

Full name : MineSweeper module

infos - infos

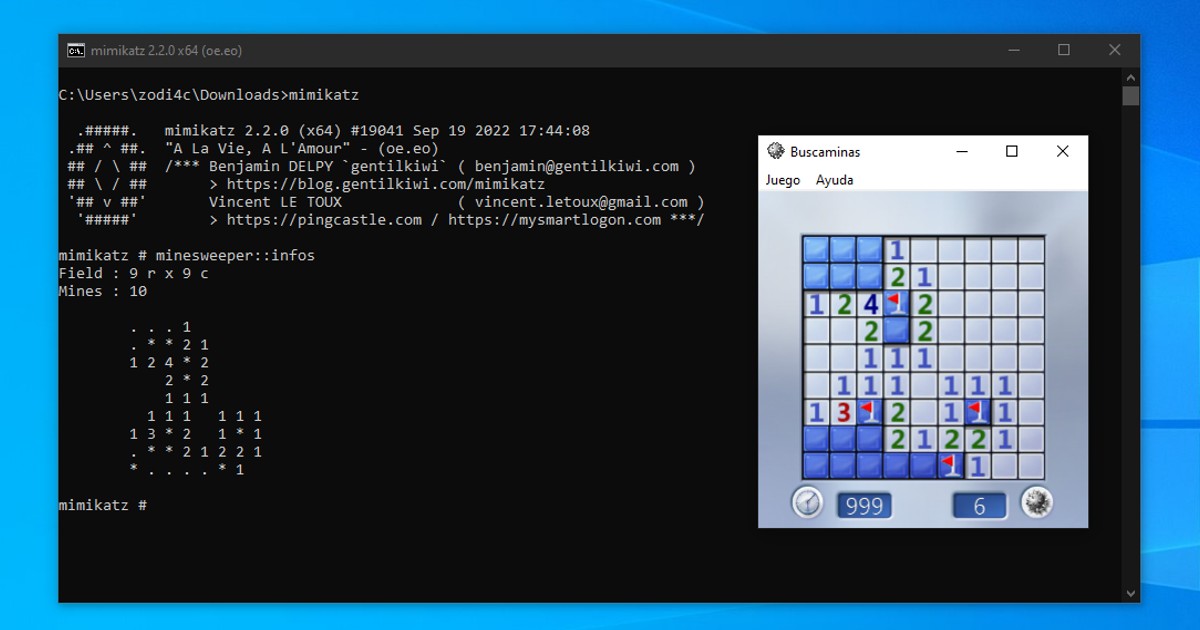

There is only one command that the minesweper module implements. That is infos, which allows the user to inspect the state of an ongoing Minesweeper game in the victim device. When executed, mimikatz searches for an existing Minesweeper process in the system, connects to it, and searches within memory the data structure used to hold the game data, then parsing it and displaying the board to the user.

While not very consequential for the usual activities of a penetration tester, it demonstrates some of the techniques widely used in mimikatz implementation: how to connect to a remote process and parse its content, in order to retrieve data that the user is not supposed to access.

Having set our goal, let’s see what is the mimikatz way of breaking into Minesweeper!

Before starting

First, let’s establish some baselines for this post. Our objective is to have a look at the internals of mimikatz and dissect one of its most basic modules. While we will be using the Rust programming language throughout, I’ll assume that the reader has some fluidity reading and working with code written in Rust. Otherwise, if you have an interest on picking up the language, I’d recommend to start by checking out The Book, which will teach you the basic principles of Rust.

For the development of this project, we will be using some crates that will greatly aid us in our task. Some of them are specifically used for the integration of some functionality in our application and will be introduced as needed in later sections. Other crates, however, are widely used throughout this article, so I’ll briefly introduce them now.

Due to the nature of the task that we want to accomplish, is foreseeable that we will need to interact with the Windows API. While there are a few crates that would allow us to do this, we will go with the official implementation by Microsoft. Specifically, we will use the windows crate, which provides an “idiomatic way for Rust developers to call Windows APIs”1.

As we will be dealing with different kind of errors, we will also use anyhow for opaque error-handling. Ideally, a solution that uses both anyhow and thiserror would make for more robust code — however, it would also add an extra layer of complexity, which I don’t consider necessary for the PoC code that we are going for.

All the relevant

usestatements have not been included for the sake of brevity, but can be found in the final repository of the project2.

Delving into the code

We’ll start by cloning the mimikatz repository and opening it up with Visual Studio Code, as using and IDE will make it easier to follow around the implementation of functions throughout different files.

For navigating into the implementation of a given functionality, hold

Controland click on the name of the symbol. If you want to return to a previous location, you can go back using theAlt + ←shortcut.

Searching for the keyword “minesweeper” in the file explorer hints at the kuhl_m_minesweeper.c file, where most of the functionality of this module is implemented. This file defines two functions:

kuhl_m_minesweeper_infos(), called when theminesweeper::infoscommand is executed.kuhl_m_minesweeper_infos_parseField(), a helper function for parsing the game board data structure.

First things first, let’s examine what the kuhl_m_minesweeper_infos function does.

Accessing the process

The first 10 lines of kuhl_m_minesweeper_infos contains declarations of variables used during the span of the function — we’ll come back to these as needed during the code analysis.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

if(kull_m_process_getProcessIdForName(L"minesweeper.exe", &dwPid))

{

if(hProcess = OpenProcess(PROCESS_VM_READ | PROCESS_VM_OPERATION | PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION, FALSE, dwPid))

{

// ...

CloseHandle(hProcess);

}

else PRINT_ERROR_AUTO(L"OpenProcess");

}

else PRINT_ERROR(L"No MineSweeper in memory!\n");

We then get to the first piece of functionality performed by the module. In line 1 of the previous code snippet, the kull_m_process_getProcessIdForName function is invoked. Thankfully, its name is pretty descriptive: it returns the PID of a running process in the system, given the name of its executable file.

Having obtained the target process’ PID, a call to the OpenProcess API is performed in line 3, returning an open handle for referencing the process. As we will be reading another process’ memory space, we will need to pass this handle to further calls to the WinAPI.

It is also important to note that this handle should be closed when we are done interacting with the Minesweeper process (even if we are finishing execution early due to an error), which is done through a call to CloseHandle, as shown at line 6.

Let’s start porting this functionality into Rust. To facilitate cross-referencing between codebases, we will keep functions defined in modules with similar names to its mimikatz counterpart. We will keep process-related functions in the process.rs module, equivalent to the kull_m_process.c library.

First, we will define a pid_by_name function. While the original mimikatz code queries the NtQuerySystemInformation internal Windows API to find the corresponding PID, I decided to go through the easier route and use already existing code to handle this functionality. The sysinfo crate can be used to query the OS for information such as memory usage or running processes, which we’ll use in our function definition:

1

2

3

4

5

pub fn pid_by_name(process_name: &str) -> Option<u32> {

let system = System::new_all();

let mut processes = system.processes_by_exact_name(process_name);

(*processes).next().map(|process| process.pid().as_u32())

}

We can now call this wrapper from lib.rs, where we will define the info function, analogous to the mineswepper::infos command:

1

2

3

4

5

pub fn info() -> Result<()> {

let Some(pid) = process::pid_by_name("Minesweeper.exe") else {

bail!("no minesweeper in memory!");

};

}

We can now add the call to OpenProcess. Of course, as we will be interfacing with C-written code, we will have to mark our code as unsafe and cast the arguments to the equivalent C types as needed:

1

2

3

4

5

6

let h_process: HANDLE = OpenProcess(

PROCESS_VM_READ | PROCESS_VM_OPERATION | PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION,

false,

pid,

)

.context("failed to open process")?;

The nice thing of using the windows crate as opposed to the windows-sys crate is that it (most of the time) provides abstractions closer to the Rust way of doing things. Here, we can see that the OpenProcess binding returns a Result enum that we can easily match for any generated errors.

We now have a HANDLE instance that corresponds to the Minesweeper process. Great! Let’s move on to the next line of the original code:

1

2

3

4

if(kull_m_memory_open(KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_PROCESS, hProcess, &aRemote.hMemory))

{

// ...

}

Huh… This line is not that immediately obvious to understand as the ones we have covered so far. Let’s take a look at the function definition:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

BOOL kull_m_memory_open(IN KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE Type, IN HANDLE hAny, OUT PKULL_M_MEMORY_HANDLE *hMemory)

{

// ...

*hMemory = (PKULL_M_MEMORY_HANDLE) LocalAlloc(LPTR, sizeof(KULL_M_MEMORY_HANDLE));

if(*hMemory)

{

(*hMemory)->type = Type;

switch (Type)

{

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_OWN:

// ...

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_PROCESS:

if((*hMemory)->pHandleProcess = (PKULL_M_MEMORY_HANDLE_PROCESS) LocalAlloc(LPTR, sizeof(KULL_M_MEMORY_HANDLE_PROCESS)))

{

(*hMemory)->pHandleProcess->hProcess = hAny;

status = TRUE;

}

break;

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_FILE:

// ...

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_PROCESS_DMP:

// ...

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_KERNEL:

// ...

default:

break;

}

// ...

}

Analyzing the function and its involved struct types, we can infer that it is meant to cast a generic C HANDLE to a custom data type defined by mimikatz. In this case, PKULL_M_MEMORY_HANDLE_PROCESS is just a wrapper for the process handle:

1

2

3

4

typedef struct _KULL_M_MEMORY_HANDLE_PROCESS

{

HANDLE hProcess;

} KULL_M_MEMORY_HANDLE_PROCESS, *PKULL_M_MEMORY_HANDLE_PROCESS;

Encoding semantically different handles as different types is a pragmatic way of enforcing some type safety in the internals of the application, as a file handle cannot be accidentally passed into a function that accepts a process handle as its argument. mimikatz defines seven different kinds of memory accesses that may be performed:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

typedef enum _KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE

{

KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_OWN,

KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_PROCESS,

KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_PROCESS_DMP,

KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_KERNEL,

KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_KERNEL_DMP,

KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_HYBERFILE,

KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_FILE,

} KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE;

This enumeration is pretty straightforwards to port to Rust. We can even leverage this enum to wrap the HANDLE and enforce additional type-checking, merging the two previous ideas into one:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

#[allow(dead_code)]

pub enum MemoryHandle {

Own,

Process(HANDLE),

File(HANDLE),

Kernel(HANDLE),

Dump,

// ...

}

Although we will only use one of these values, the Process variant, I defined some of them anyway to better convey the meaning of this enumeration for further development of the codebase. A tuple struct could have been sufficient otherwise, following the newtype pattern.

As remarked earlier, we need to call CloseHandle on the returned pointer, to ensure that the resource is safely freed by the OS when we terminate our program. A common way of dealing with this responsibility is to implement the RAII pattern, so that the handle is automatically closed upon object destruction. To achieve this, we will implement the Drop trait in the MemoryHandle enum:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

impl Drop for MemoryHandle {

fn drop(&mut self) {

match self {

Self::Process(handle) => unsafe {

CloseHandle(*handle);

},

_ => unimplemented!("Drop trait not implemented for {:?}", &self),

}

}

}

I also went ahead and implemented the Deref trait, so that it’s easier to work with the original HANDLE value. We may now wrap our retrieved handle within the MemoryHandle type, updating our previous unsafe block as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

let a_remote = unsafe {

let h_process: HANDLE = OpenProcess(

PROCESS_VM_READ | PROCESS_VM_OPERATION | PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION,

false,

pid,

)

.context("failed to open process")?;

MemoryHandle::Process(h_process)

};

Excellent! We can now safely make API calls to interact with the target process.

Where from here?

We can move on now onto the next few lines of the infos function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

if(kull_m_process_peb(aRemote.hMemory, &Peb, FALSE))

{

aRemote.address = Peb.ImageBaseAddress;

if(kull_m_process_ntheaders(&aRemote, &pNtHeaders))

{

sMemory.kull_m_memoryRange.kull_m_memoryAdress.address = (LPVOID) pNtHeaders->OptionalHeader.ImageBase;

sMemory.kull_m_memoryRange.size = pNtHeaders->OptionalHeader.SizeOfImage;

// ...

}

else PRINT_ERROR(L"Minesweeper NT Headers\n");

}

else PRINT_ERROR(L"Minesweeper PEB\n");

Let’s step through this code. In line 1, the kull_m_process_peb function is executed, returning a pointer to the PEB structure, a user-mode data structure where Windows stores some relevant information about a process. In line 3, we can see that we specifically need the ImageBaseAddress field of the PEB, which holds the address where the Minesweeper image was loaded in memory.

The Image Base address is used in the next key piece of functionality, in line 4, where the kull_m_process_ntheaders is used to retrieve the NT headers structure. This is one of the first headers of the PE file format, and specifies information about the executable file and how it can be loaded into memory and executed. This information will be relevant as we search for the game board data structure that holds the information about the current game of Minesweeper.

Let’s go through each of these steps, one at a time. A simplified version of the kull_m_process_peb can be found in the code snippet below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

BOOL kull_m_process_peb(PKULL_M_MEMORY_HANDLE memory, PPEB pPeb, BOOL isWOW)

{

BOOL status = FALSE;

PROCESS_BASIC_INFORMATION processInformations;

HANDLE hProcess = memory->pHandleProcess->hProcess;

KULL_M_MEMORY_ADDRESS aBuffer = {pPeb, &KULL_M_MEMORY_GLOBAL_OWN_HANDLE};

KULL_M_MEMORY_ADDRESS aProcess = {NULL, memory};

PROCESSINFOCLASS info;

ULONG szPeb, szBuffer, szInfos;

LPVOID buffer;

switch (memory->type)

{

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_PROCESS:

if (NT_SUCCESS(NtQueryInformationProcess(hProcess, info, buffer, szBuffer, &szInfos))

&& (szInfos == szBuffer)

&& processInformations.PebBaseAddress

){

aProcess.address = processInformations.PebBaseAddress;

status = kull_m_memory_copy(&aBuffer, &aProcess, szPeb);

}

break;

}

return status;

}

I have trimmed some variable definitions and focused on the relevant x64 functionality, as we will limit our tool to this architecture for simplicity. This function mainly calls the NtQueryInformationProcess API, which has the following prototype according to its documentation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

__kernel_entry NTSTATUS NtQueryInformationProcess(

[in] HANDLE ProcessHandle,

[in] PROCESSINFOCLASS ProcessInformationClass,

[out] PVOID ProcessInformation,

[in] ULONG ProcessInformationLength,

[out, optional] PULONG ReturnLength

);

The ProcessHandle will correspond to the open handle that we own for the target process. The ProcessInformationClass is one of the most relevant parameters: it holds a value from the PROCESSINFOCLASS enumeration, and it establishes what information must be retrieved by this API call. In this case, we are interested in accessing the PEB structure, so we must provide the ProcessBasicInformation value, corresponding to 0. The rest of arguments relate to the output of this API call — where to store the output, the size of the allocated memory and how much of it was occupied.

The API will return a PROCESS_BASIC_INFORMATION structure, which holds a pointer to where the PEB is located, stored in the PebBaseAddress field. This value is accessed in the previous code snippet at line 19, and then used in a call to the kull_m_memory_copy function. Let’s review it!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

BOOL kull_m_memory_copy(OUT PKULL_M_MEMORY_ADDRESS Destination, IN PKULL_M_MEMORY_ADDRESS Source, IN SIZE_T Length)

{

// ...

switch (Destination->hMemory->type)

{

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_OWN:

switch (Source->hMemory->type)

{

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_OWN:

// ...

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_PROCESS:

status = ReadProcessMemory(Source->hMemory->pHandleProcess->hProcess, Source->address, Destination->address, Length, NULL);

break;

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_PROCESS_DMP:

// ...

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_FILE:

// ...

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_KERNEL:

// ...

default:

break;

}

break;

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_PROCESS:

// ...

}

// ...

return status;

}

Okay, so it seems that this function takes a source to copy from and a destination to store the output of the operation. I’ve highlighted the only case that we will consider in this post: copying from another process’ memory space to ours. This is achieved through a call to the ReadProcessMemory API, simply by passing the process handle and indicating how many bytes we want to read.

Retrieving the PEB

We are now equipped with all the knowledge necessary to port the code in charge of retrieving the PEB to Rust. Let’s start backwards, beginning with the copy functionality.

We will simplify, and assume that the destination will always be our own process, as this is the case in the majority of the

mimikatzcodebase.

1

2

3

4

5

6

pub unsafe fn copy<T>(source: &MemoryHandle, data_ptr: *const T) -> Result<T> {

match source {

MemoryHandle::Process(handle) => read_from_process(*handle, data_ptr),

_ => unimplemented!("copy not implemented for {:?}", source),

}

}

This function will act as a wrapper for the actual code that performs the copy, allowing us to match the value of the source MemoryHandle to the correct specific operation. Now, we need to write down the read_from_process function. Luckily, while searching documentation on how to properly use the ReadProcessMemory API in Rust, I came across a Mozilla library that does exactly what we want. I re-adapted the error management to fit our needs, ending up with the following function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

unsafe fn read_from_process<T>(process: HANDLE, data_ptr: *const T) -> Result<T> {

let mut data: T = mem::zeroed();

unsafe {

ReadProcessMemory(

process,

data_ptr as *mut _,

addr_of_mut!(data) as *mut _,

mem::size_of::<T>(),

None,

)

}

.as_bool()

.then_some(data)

.ok_or(anyhow!("error reading memory of remote process"))

}

We can now read data structures from a remote process! As we will be reading the PEB, let’s define a data structure with the relevant fields that we may use. The MSDN documentation defines the PEB structure as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

typedef struct _PEB {

BYTE Reserved1[2];

BYTE BeingDebugged;

BYTE Reserved2[1];

PVOID Reserved3[2];

PPEB_LDR_DATA Ldr;

PRTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS ProcessParameters;

PVOID Reserved4[3];

PVOID AtlThunkSListPtr;

PVOID Reserved5;

ULONG Reserved6;

PVOID Reserved7;

ULONG Reserved8;

ULONG AtlThunkSListPtr32;

PVOID Reserved9[45];

BYTE Reserved10[96];

PPS_POST_PROCESS_INIT_ROUTINE PostProcessInitRoutine;

BYTE Reserved11[128];

PVOID Reserved12[1];

ULONG SessionId;

} PEB, *PPEB;

Unluckily, this description is not very helpful, as this structure is only meant to be used for internal development. We do, however, get a more descriptive definition if we query WinDbg for the definition of ntdll!_PEB:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

0:001> dt _PEB

ntdll!_PEB

+0x000 InheritedAddressSpace : UChar

+0x001 ReadImageFileExecOptions : UChar

+0x002 BeingDebugged : UChar

+0x003 BitField : UChar

+0x003 ImageUsesLargePages : Pos 0, 1 Bit

+0x003 IsProtectedProcess : Pos 1, 1 Bit

+0x003 IsImageDynamicallyRelocated : Pos 2, 1 Bit

+0x003 SkipPatchingUser32Forwarders : Pos 3, 1 Bit

+0x003 IsPackagedProcess : Pos 4, 1 Bit

+0x003 IsAppContainer : Pos 5, 1 Bit

+0x003 IsProtectedProcessLight : Pos 6, 1 Bit

+0x003 IsLongPathAwareProcess : Pos 7, 1 Bit

+0x004 Mutant : Ptr32 Void

+0x008 ImageBaseAddress : Ptr32 Void

+0x00c Ldr : Ptr32 _PEB_LDR_DATA

+0x010 ProcessParameters : Ptr32 _RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS

...

This description matches with the struct defined in kull_m_process.h. Using WinDbg’s symbols for developing a better understanding of how an undescriptive piece of software works will prove to be very useful once again in a few sections. For now, however, let’s implement this structure:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

#[repr(C)]

pub struct Peb {

pub inherited_address_space: u8,

pub read_image_file_exec_options: u8,

pub being_debugged: u8,

pub bit_field: BitField,

pub mutant: HANDLE,

pub image_base_address: *mut c_void,

pub ldr: *mut PEB_LDR_DATA,

pub process_parameters: *mut RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS,

// ...

}

#[repr(C)]

pub struct BitField {

pub image_uses_large_pages: u8,

pub spare_bits: u8,

}

Great! We are now only missing the last puzzle piece: the function that actually calls NtQueryInformationProcess to retrieve the memory address of the PEB and copies it to our process:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

fn peb_process(memory: &MemoryHandle, _is_wow: bool) -> Result<Peb> {

unsafe {

let mut return_length = 0_u32;

let mut process_informations: PROCESS_BASIC_INFORMATION = mem::zeroed();

let process_information_length = mem::size_of::<PROCESS_BASIC_INFORMATION>() as u32;

NtQueryInformationProcess(

**memory,

ProcessBasicInformation,

&mut process_informations as *mut _ as _,

process_information_length,

&mut return_length as *mut u32,

)?;

ensure!(

process_information_length == return_length,

"unexpected result from NtQueryInformationProcess"

);

memory::copy(memory, process_informations.PebBaseAddress as *const Peb)

}

}

Finally, we call this function from our main info:

1

let peb = process::peb(&a_remote, false).context("unable to access process' PEB")?;

Dumping the PE headers

As previously discussed, the point of retrieving the PEB is to parse the NT headers. Now, how does mimikatz achieve this?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

BOOL kull_m_process_ntheaders(PKULL_M_MEMORY_ADDRESS pBase, PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS *pHeaders)

{

BOOL status = FALSE;

IMAGE_DOS_HEADER headerImageDos;

KULL_M_MEMORY_ADDRESS aBuffer = {&headerImageDos, &KULL_M_MEMORY_GLOBAL_OWN_HANDLE}, aRealNtHeaders = {NULL, &KULL_M_MEMORY_GLOBAL_OWN_HANDLE}, aProcess = {NULL, pBase->hMemory};

DWORD size;

if (kull_m_memory_copy(&aBuffer, pBase, sizeof(IMAGE_DOS_HEADER)) && headerImageDos.e_magic == IMAGE_DOS_SIGNATURE)

{

aProcess.address = (PBYTE)pBase->address + headerImageDos.e_lfanew;

if (aBuffer.address = LocalAlloc(LPTR, sizeof(DWORD) + IMAGE_SIZEOF_FILE_HEADER))

{

if (kull_m_memory_copy(&aBuffer, &aProcess, sizeof(DWORD) + IMAGE_SIZEOF_FILE_HEADER) && ((PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)aBuffer.address)->Signature == IMAGE_NT_SIGNATURE)

;

{

size = (((PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)aBuffer.address)->FileHeader.Machine == IMAGE_FILE_MACHINE_I386) ? sizeof(IMAGE_NT_HEADERS32) : sizeof(IMAGE_NT_HEADERS64);

if (aRealNtHeaders.address = (PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)LocalAlloc(LPTR, size))

{

status = kull_m_memory_copy(&aRealNtHeaders, &aProcess, size);

if (status)

*pHeaders = (PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)aRealNtHeaders.address;

else

LocalFree(aRealNtHeaders.address);

}

}

LocalFree(aBuffer.address);

}

}

return status;

}

Okay, that’s a bit unclear for me at first sight, so let’s break it down:

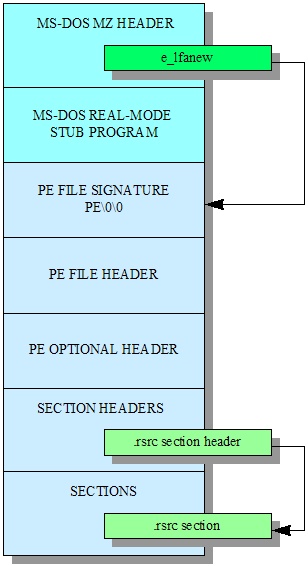

- In line 8, the Image Base address is used to copy the DOS header over to our process. There is a sanity check in place, which ensures that the

e_magicfield is valid. - In line 10, the address of the NT header is calculated by offsetting the Image Base by the value indicated by the

e_lfanewfield of the DOS header. - In line 13, the first two fields of the NT headers are copied: the

Signature, and theFileHeader. As a sanity check, the signature is checked against its expected value. - In line 16, the

Machinefield of the File Header is used to determine the size of the complete NT header. This is due to the size of this structure being architecture-dependent: theOptionalHeaderfield may hold anIMAGE_NT_HEADERS32inx86executables, or anIMAGE_NT_HEADERS64inx64PE files. - In line 19, the whole NT headers are copied over to the current process memory space.

PE headers diagram from OSDev.org

PE headers diagram from OSDev.org

That took a few steps, but we now know how to extract the NT headers from the Minesweeper process. The caveat with this implementation is that the output of this function may have a different size depending on the architecture in which the target executable was compiled. We can not implement this logic directly into Rust, as all types must have a known size at compile time.

We can get around this limitation by expressing the result as an enumeration, which must be unwrapped by the caller to determine the appropriate handling:

1

2

3

4

pub enum ImageNtHeaders {

X86(IMAGE_NT_HEADERS32),

X64(IMAGE_NT_HEADERS64),

}

While at it, let’s also implement a validation function that checks if the NT headers structure is valid:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

impl ImageNtHeaders {

fn is_valid(&self) -> bool {

match self {

Self::X86(header) => header.Signature == IMAGE_NT_SIGNATURE,

Self::X64(header) => header.Signature == IMAGE_NT_SIGNATURE,

}

}

}

We can now move on to implementing the actual retrieval function. We’ll start by copying the DOS header:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

pub unsafe fn nt_headers(

process: &MemoryHandle,

image_base: *const c_void,

) -> Result<ImageNtHeaders> {

let dos_header: IMAGE_DOS_HEADER = memory::copy(process, image_base as *const _)?;

ensure!(

dos_header.e_magic == IMAGE_DOS_SIGNATURE,

"invalid DOS signature"

);

We now copy the first two fields of the NT headers, which are always the same size despite the executable architecture. We could define a simple enumeration for temporarily holding this data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

#[repr(C)]

struct ImageNtHeadersCommon {

signature: u32,

file_header: IMAGE_FILE_HEADER,

// optional header omitted (architecture dependant)

}

With our current tool set, we can now easily retrieve this information from the target process:

1

2

let p_nt_headers = image_base.offset(dos_header.e_lfanew as isize);

let nt_common: ImageNtHeadersCommon = memory::copy(process, p_nt_headers as *const _)?;

Now, we can check the Machine field of the file_header attribute to check the architecture of the target. We then copy an IMAGE_NT_HEADERS32 or an IMAGE_NT_HEADERS64, as necessary.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

match nt_common.file_header.Machine {

IMAGE_FILE_MACHINE_I386 => {

let headers_32: IMAGE_NT_HEADERS32 =

memory::copy(process, p_nt_headers as *const _)?;

ImageNtHeaders::X86(headers_32)

}

_ => {

let headers_64: IMAGE_NT_HEADERS64 =

memory::copy(process, p_nt_headers as *const _)?;

ImageNtHeaders::X64(headers_64)

}

}

We are only left with some sanity checks, and we are good to go!

1

2

3

4

nt_headers

.is_valid()

.then_some(nt_headers)

.ok_or(anyhow!("invalid NT signature"))

We can now use this function to retrieve the Image Base and the Image Size, which will be useful for parsing Minesweeper’s memory later on.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

let ntheaders = process::nt_headers(&a_remote, peb.image_base_address)

.context("unable to access process' NT header")?;

let (image_base, image_size) = match ntheaders {

ImageNtHeaders::X64(headers) => (

headers.OptionalHeader.ImageBase as *const _,

headers.OptionalHeader.SizeOfImage,

),

ImageNtHeaders::X32(_) => bail!("x86 minesweeper not yet supported"),

};

Game Hacking 101

Now that we have the basic information that we needed from the target process, let’s actually get to the game hacking part of the code! The next line of the ìnfos original function is included below:

1

2

3

4

5

if(kull_m_memory_search(&aBuffer, sizeof(PTRN_WIN6_Game_SafeGetSingleton), &sMemory, TRUE))

{

aRemote.address = (PBYTE) sMemory.result + OFFS_WIN6_ToG;

// ...

} else PRINT_ERROR(L"Search is KO\n");

Okay, it seems that mimikatz is looking for the address of a certain byte pattern in the process memory, and calculating an offset from it. The constants used are defined earlier in the same file:

1

2

BYTE PTRN_WIN6_Game_SafeGetSingleton[] = {0x48, 0x89, 0x44, 0x24, 0x70, 0x48, 0x85, 0xc0, 0x74, 0x0a, 0x48, 0x8b, 0xc8, 0xe8};

LONG OFFS_WIN6_ToG = -21;

Okay, this doesn’t seem so bad to implement! But wait. What does it mean? What does this pattern represent? Why is such an specific offset used? We may as well blindly implement this functionality into our code and it will be guaranteed to work, but we would be missing the whole point of this article! Remember our goal:

Re-implement the tools that you commonly use to better understand its underlying functionality.

In order to actually understand what mimikatz is doing here, we will need to do more than just reading code. So, let’s dust off our debugging tools, and let’s investigate what’s happening here!

Getting lucky with WinDbg

As with any study of an unknown executable, it is best to adopt a dual approach and make use of dynamic and static analysis tools, such a debugger and a disassembler. In this post, we will go with WinDbg and Ghidra, out of personal preference.

As I opened the Minesweeper process with WinDbg, I noticed something interesting:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

0:010> lm

start end module name

00007ff7`23400000 00007ff7`234db000 Minesweeper (pdb symbols) c:\symbols\MineSweeper.pdb\703075879C2C4B41AC79B03C1CEC33D81\MineSweeper.pdb

00007ffd`c0c00000 00007ffd`c0dce000 d3d9 (deferred)

00007ffd`d2800000 00007ffd`d292d000 mfperfhelper (deferred)

00007ffd`ee070000 00007ffd`ee2c9000 wmvcore (deferred)

00007ffd`f5be0000 00007ffd`f5d85000 gdiplus (deferred)

It seems that WinDbg was able to retrieve the symbols file for this process from the Microsoft Internet Symbol Server. That’s excellent news! We will be able to take a look at the internals of this application using the original names for all the declared functions and variables, making our investigation much easier. The finding of these symbols also mean that our disassembler output is a bit less valuable now, so we’ll also leave Ghidra aside for now.

We’ll start by looking for the PTRN_WIN6_Game_SafeGetSingleton pattern defined in mimikatz. A simple search for this byte sequence yields a single match in the process memory:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

0:010> s -b minesweeper L?DB000 48 89 44 24 70 48 85 c0 74 0a 48 8b c8 e8

00007ff7`2342bc44 48 89 44 24 70 48 85 c0-74 0a 48 8b c8 e8 fe cf H.D$pH..t.H.....

0:010> !address 00007ff7`2342bc44

Usage: Image

Base Address: 00007ff7`23401000

End Address: 00007ff7`2349f000

Region Size: 00000000`0009e000 ( 632.000 kB)

State: 00001000 MEM_COMMIT

Protect: 00000020 PAGE_EXECUTE_READ

Type: 01000000 MEM_IMAGE

Allocation Base: 00007ff7`23400000

...

We can also see that the returned address corresponds to the executable code section of the program. This is what is usually referred to as an AOB pattern in game hacking, where a unique pattern of bytes in the executable is used to dynamically retrieve a relevant instruction for modification.

If we disassemble the instructions in the found address, we can see that they, indeed, match the AOB pattern defined in the mimikatz source code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

0:010> u 00007ff7`2342bc44

Minesweeper!Game::SafeGetSingleton+0x2c:

00007ff7`2342bc44 4889442470 mov qword ptr [rsp+70h],rax

00007ff7`2342bc49 4885c0 test rax,rax

00007ff7`2342bc4c 740a je Minesweeper!Game::SafeGetSingleton+0x40 (00007ff7`2342bc58)

00007ff7`2342bc4e 488bc8 mov rcx,rax

00007ff7`2342bc51 e8fecfffff call Minesweeper!Game::Game (00007ff7`23428c54)

However, we are not really interested in these specific instructions. If we recall the previous kuhl_m_minesweeper.c code snippet, an offset of -21 bytes from the resulting address is calculated and stored for further use. Through WinDbg, we may find out that the referenced address is part of the following instruction:

1

00007ff7`2342bc2c 48833d04ee070000 cmp qword ptr [Minesweeper!Game::G (00007ff7`234aaa38)],0

It seems that this instruction is comparing the G variable with 0. The offset calculated by mimikatz points to the 04ee0700 part of the cmp instruction, which indicates the offset in bytes to where the G variable is stored in memory. So it seems that G is important, but what is it?

The next few lines of the disassembler can give us a hint:

1

2

3

4

00007ff7`2342bc2c 48833d04ee070000 cmp qword ptr [Minesweeper!Game::G (00007ff7`234aaa38)],0

00007ff7`2342bc34 0f85d3000000 jne Minesweeper!Game::SafeGetSingleton+0xf5 (00007ff7`2342bd0d)

00007ff7`2342bc3a b928010000 mov ecx,128h

00007ff7`2342bc3f e854340600 call Minesweeper!operator new (00007ff7`2348f098)

If G is equal to 0, then the new operator is invoked. This tells us that G must be a pointer, probably to the structure that is in charge of managing the game status. Indeed, later in the infos function of the Minesweeper module we found that G is dereferenced and used to build a STRUCT_MINESWEEPER_GAME structure:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

typedef struct _STRUCT_MINESWEEPER_GAME

{

PVOID Serializer;

PVOID pNodeBase;

PVOID pBoardCanvas;

PSTRUCT_MINESWEEPER_BOARD pBoard;

PSTRUCT_MINESWEEPER_BOARD pBoard_WIN7x86;

} STRUCT_MINESWEEPER_GAME, *PSTRUCT_MINESWEEPER_GAME;

We finally have found the game board! And, in the process, we have gained a better understanding of the kind of investigations performed by mimikatz developers to implement its functionality. Let’s return to our first objective: re-writing this code in Rust.

Searching for patterns

Our first challenge will be to implement a search function that will allow us to identify a byte pattern within another’s process memory. As always, if in doubt, we shall ask ourselves: What Would mimikatz Do?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

BOOL kull_m_memory_search(IN PKULL_M_MEMORY_ADDRESS Pattern, IN SIZE_T Length, IN PKULL_M_MEMORY_SEARCH Search, IN BOOL bufferMeFirst)

{

// ...

switch (Pattern->hMemory->type)

{

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_OWN:

switch (Search->kull_m_memoryRange.kull_m_memoryAdress.hMemory->type)

{

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_OWN:

for (CurrentPtr = (PBYTE)Search->kull_m_memoryRange.kull_m_memoryAdress.address; !status && (CurrentPtr + Length <= limite); CurrentPtr++)

status = RtlEqualMemory(Pattern->address, CurrentPtr, Length);

CurrentPtr--;

break;

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_PROCESS:

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_FILE:

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_KERNEL:

if (sBuffer.kull_m_memoryRange.kull_m_memoryAdress.address = LocalAlloc(LPTR, Search->kull_m_memoryRange.size))

{

if (kull_m_memory_copy(&sBuffer.kull_m_memoryRange.kull_m_memoryAdress, &Search->kull_m_memoryRange.kull_m_memoryAdress, Search->kull_m_memoryRange.size))

if (status = kull_m_memory_search(Pattern, Length, &sBuffer, FALSE))

CurrentPtr = (PBYTE)Search->kull_m_memoryRange.kull_m_memoryAdress.address + (((PBYTE)sBuffer.result) - (PBYTE)sBuffer.kull_m_memoryRange.kull_m_memoryAdress.address);

LocalFree(sBuffer.kull_m_memoryRange.kull_m_memoryAdress.address);

}

break;

case KULL_M_MEMORY_TYPE_PROCESS_DMP:

// ...

default:

break;

}

break;

default:

break;

}

// ...

}

The implementation of this functionality is pretty interesting. First, the switch statement in line 4 checks where the target memory space resides. In this case, as we are searching within another process, the case in line 14 is triggered. This block of code will then take the provided base address and size for the search, and will copy the entire thing from the target process to our own memory space.

Then, the function calls itself, this time passing the memory address of the block that it just copied. The case statement at line 6 will trigger, performing the actual search for the pattern. When it finishes, the execution flow will backtrack to the earlier search call, mapping the address of the finding from mimikatz memory space to where it resides in the target process, as shown in line 21.

In order to make this work in our codebase, we will first need to add the ability to copy raw chunks of bytes from the target process. We implemented before a generic copy function, but it requires that we specify a type T where the data will be stored. As we don’t really have a type that represents the exact amount of bytes that the Minesweeper image occupies, we will have to come up with an alternative.

Thankfully, the Mozilla project that we discovered earlier will help us again! They found a similar problem to ours, and implemented a read_array_from_process function, shown below with some adaptations to accommodate for the error handling that use throughout our application:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

unsafe fn read_array_from_process<T>(

process: HANDLE,

data_ptr: *const T,

count: usize,

) -> Result<Vec<T>>

where

T: Clone + Default,

{

let mut vec = vec![Default::default(); count];

let size = mem::size_of::<T>()

.checked_mul(count)

.ok_or(anyhow!("invalid read, overflow in array size"))?;

unsafe {

ReadProcessMemory(

process,

data_ptr as *mut _,

vec.as_mut_ptr() as *mut _,

size,

None,

)

}

.as_bool()

.then_some(vec)

.ok_or(anyhow!("error reading memory of remote process"))

}

For the sake of being consistent with our public API, let’s wrap this code in a public copy_array function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

pub unsafe fn copy_array<T>(

memory: &MemoryHandle,

data_ptr: *const T,

count: usize,

) -> Result<Vec<T>>

where

T: Clone + Default,

{

match memory {

MemoryHandle::Process(handle) => read_array_from_process(*handle, data_ptr, count),

_ => unimplemented!("copy_array not implemented for {:?}", memory),

}

}

We can now easily copy chunks of bytes from the target process and temporarily store them in a Vec<u8>. Great!

We’re almost done implementing the search functionality, as we will offload the responsibility of performing the search to a more specialized crate. I decided to go for the memchr crate, as it seems to be widely used and frequently updated. The implementation then boils down to this code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

pub unsafe fn search(

pattern: &[u8],

memory: &MemoryHandle,

base: *const c_void,

size: u32,

) -> Result<*const c_void> {

match memory {

MemoryHandle::Process(_) | MemoryHandle::File(_) | MemoryHandle::Kernel(_) => {

let data: Vec<u8> = copy_array(memory, base as *const _, size as usize)

.context("failed to copy haystack")?;

let match_offset = memmem::find(&data, pattern).ok_or(anyhow!("pattern not found"))?;

Ok(base.add(match_offset))

}

_ => unimplemented!("search not implemented for {:?}", memory),

}

}

In line 9 we use our recently defined copy_array function to retrieve a buffer with the entire program image. Then, we call memchr::memmem::find at line 11 to do the actual search of the AOB pattern for us and, finally, at line 12, we return the memory address where the match was found.

In-memory navigation

We are almost done now! Let’s implement the logic for locating and retrieving the game board. We earlier left kuhl_m_minesweeper.c code at this point:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

if(kull_m_memory_search(&aBuffer, sizeof(PTRN_WIN6_Game_SafeGetSingleton), &sMemory, TRUE))

{

aRemote.address = (PBYTE) sMemory.result + OFFS_WIN6_ToG;

aBuffer.address = &offsetTemp;

if(kull_m_memory_copy(&aBuffer, &aRemote, sizeof(LONG)))

{

// ...

}

} else PRINT_ERROR(L"Search is KO\n");

This code is responsible for locating the offset from the cmp instruction that we found earlier to the memory address of the G variable, which stores a pointer to the game board. The offset is sizeof(LONG) bytes long or, in other words, 4 bytes in size.

This is pretty straightforwards to implement, using the functions that we have already defined in the memory.rs module:

1

2

3

4

5

6

unsafe {

let get_singleton_instruction =

memory::search(&WIN6_SAFE_GET_SINGLETON, &a_remote, image_base, image_size)?;

let p_g_offset = get_singleton_instruction.offset(OFFS_WIN6_TO_G);

let g_offset: u32 = memory::copy(&a_remote, p_g_offset as *const _)?;

}

Alright, let’s keep on moving. What’s next in the original code?

1

2

3

4

5

6

aRemote.address = (PBYTE) aRemote.address + 1 + sizeof(LONG) + offsetTemp;

aBuffer.address = &G;

if(kull_m_memory_copy(&aBuffer, &aRemote, sizeof(PVOID)))

{

// ...

} else PRINT_ERROR(L"G copy\n");

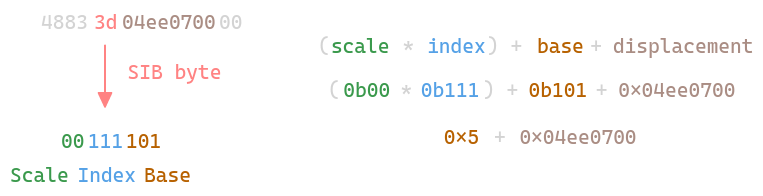

If you are anything like me, line 1 may come as a surprise. Initially, I could understand that the value that we just read was added to the address of the cmp instruction, as it indicates a relative offset from it. But, why are we adding an additional displacement of 5 bytes?

This turned out to be a quite deep rabbit hole to research. The cmp instruction used belongs to an extension of the x86 and x86-64 instruction set architecture, which uses the VEX coding scheme. In the encoding of the instruction, the SIB byte is used to indicate additional addressing for complex scenarios. In this case, the SIB byte indicates that an additional displacement of 5 bytes must be considered to reach the target address for the operation.

x86-64 cmp instruction dissection.

Now, knowing why 5 bytes are added to the offset, let’s adapt the code to Rust and copy the G variable to our process:

1

2

let p_g = p_g_offset.offset(1 + std::mem::size_of::<u32>() as isize + g_offset as isize);

let p_game: *const MinesweeperGame = memory::copy(&a_remote, p_g as *const _)?;

We finally have a pointer to the game structure we’ve been seeking this entire time! You might have noticed that we’ve casted the retrieved pointer as a *const MinesweeperGame. This structure has been defined in our code accordingly to mimikatz original description, which was showcased earlier:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#[repr(C)]

struct MinesweeperGame {

serializer: *mut c_void,

p_node_base: *mut c_void,

p_board_canvas: *mut c_void,

p_board: *mut MinesweeperBoard,

}

Similarly, the MinesweeperBoard and MinesweeperElement structures were defined, following a similar process:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

typedef struct _STRUCT_MINESWEEPER_REF_ELEMENT

{

DWORD cbElements;

DWORD unk0;

DWORD unk1;

PVOID elements;

DWORD unk2;

DWORD unk3;

} STRUCT_MINESWEEPER_REF_ELEMENT, *PSTRUCT_MINESWEEPER_REF_ELEMENT;

typedef struct _STRUCT_MINESWEEPER_BOARD

{

PVOID Serializer;

DWORD cbMines;

DWORD cbRows;

DWORD cbColumns;

// ...

PSTRUCT_MINESWEEPER_REF_ELEMENT ref_visibles;

PSTRUCT_MINESWEEPER_REF_ELEMENT ref_mines;

DWORD unk12;

DWORD unk13;

} STRUCT_MINESWEEPER_BOARD, *PSTRUCT_MINESWEEPER_BOARD;

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

#[repr(C)]

struct MinesweeperElement {

cb_elements: u32,

unk0: u32,

unk1: u32,

elements: *mut c_void,

unk2: u32,

unk3: u32,

}

#[repr(C)]

struct MinesweeperBoard {

serializer: *mut c_void,

cb_mines: u32,

cb_rows: u32,

cb_columns: u32,

// ...

ref_visibles: *mut MinesweeperElement,

ref_mines: *mut MinesweeperElement,

unk12: u32,

unk13: u32,

}

With all the puzzle pieces ready and laid out, let’s retrieve the actual game board object from memory:

1

2

let game: MinesweeperGame = memory::copy(&a_remote, p_game)?;

let board: MinesweeperBoard = memory::copy(&a_remote, game.p_board)?;

At this point, we are only left with the parsing and formatting of the board data to show to the final user. Phew!

Parsing the board

Now that we have copied the MinesweeperBoard data structure to our own process, we are left with the task of understanding the encoding of the game board. Although we do have a local copy of the MinesweeperBoard, it only holds pointers to other regions of memory where the actual state is stored, so we are not yet done interacting with the process.

The actual parsing logic deviates from the topic that I wanted this write-up to revolve on — the basics on how mimikatz interacts with other processes to extract secrets. I won’t extensively cover the implemented parsing code as I’ve been doing until now, but you may check the final implementation in the GitHub repo.

Essentially, a MinesweeperBoard holds two MinesweeperElement: the ref_visibles and ref_mines elements. This first one holds information about the cells that have been already revealed to the player, while the latter holds the position of mines within the board. Each of these elements holds a pointer that, based on the context in which it is used, may be:

- A pointer to another

MinesweeperElement - A pointer to an array of

MinesweeperElement - A value, that may be 4 bytes long in the case of

ref_visiblesor 1 byte long forref_mines

The flexibility of the MinesweeperElement structure allows it to represent an entire matrix, each of its columns or a single value stored within a cell. The downside of this dynamic implementation, of course, is that it is not obvious at first sight what a MinesweeperElement means or how it should be typed, breaking some of Rust’s fundamental design choices.

Eventually, however, I transformed this abstraction into a simpler data structure to represent the board state:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

pub struct Board {

mines: u32,

rows: usize,

columns: usize,

data: Vec<Vec<ColoredString>>,

}

// Added a `new` and `insert` method for ease of use.

impl Board { /* ... */ }

// Implementation of the Display trait, to easily print the board state.

impl Display for Board {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut std::fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

for r in 0..self.rows {

write!(f, "\t")?;

for c in 0..self.columns {

write!(f, "{} ", self.data[r][c])?;

}

writeln!(f)?;

}

Ok(())

}

}

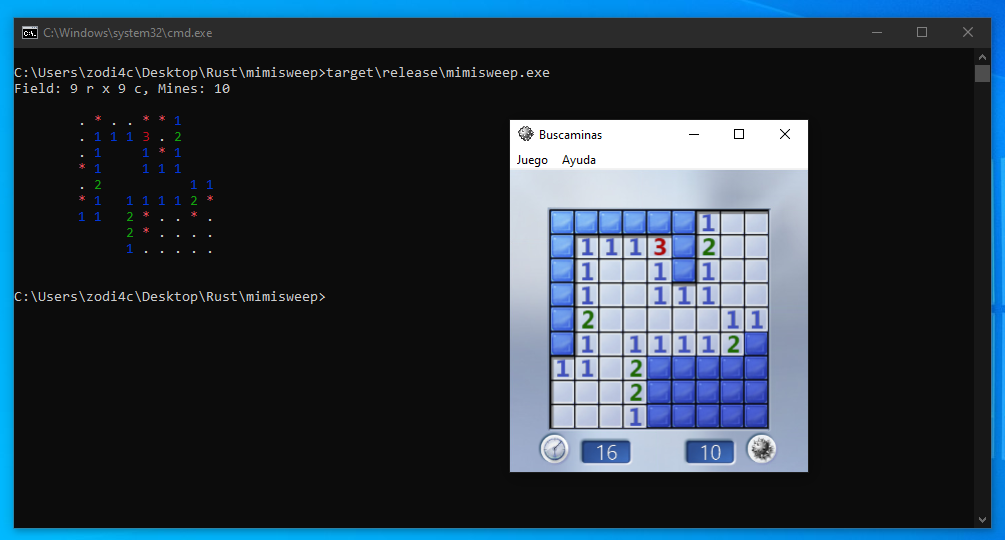

I designed the Board structure to use the ColoredString class defined in the colorize crate, as I found that the original mimikatz::minesweeper module lacks a bit of color for clarity.

Once the game board has been parsed, we can just show it on screen:

1

2

3

4

5

println!(

"Field: {} r x {} c, Mines: {}",

board.rows, board.columns, board.mines

);

println!("\n{board}");

We are finally ready to run our tool and check the final result!

Execution of the tool with the official Windows 7 Minesweeper.

Execution of the tool with the official Windows 7 Minesweeper.

Final thoughts

It’s been quite a journey! We have studied the implementation of some of the most widely used modules in the mimikatz codebase, starting with zero knowledge of the actual internals of the application. We’ve also shown how this C code may be relatively inexpensively ported into Rust, learning a thing or two about what kind of operations mimikatz perform to extract secrets from its targets.

As I stated at the beginning of this post, sometimes even the most simple modules of our most widely-used tools can surprise us with a lot of intricacy and complexity in its implementation. Re-coding part of your toolset is not only a great exercise to get comfortable with a new programming language — but also, an excellent way of gaining a deeper understanding on details that we may fail to appreciate in the busyness of an engagement.

Stay curious!

Footnotes

According to its official repository description. ↩

Note that the

v0.1.0tag of the repository is linked here instead of the main branch, as additional functionality not discussed in this post has been further added to the code. ↩